Lesson 2: Benefits of Optimal Preterm Nutrition in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

2.6 Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a devastating complication of preterm birth. Though the condition also occurs in term infants, very low birth weight (VLBW) premature infants (<1500g, <32 weeks) represent about 85% of the total cases of NEC, occurring most frequently at the lowest GAs. In a cohort of 9575 VLBW infants born at GA 22-28 weeks the overall incidence of NEC was 11% (Stoll et al. 2010). Morbidity and mortality are high. The pathophysiology leading to the endpoint of bowel necrosis is not fully understood and is probably multifactorial, and it likely differs between term and preterm infants (Neu 2014).

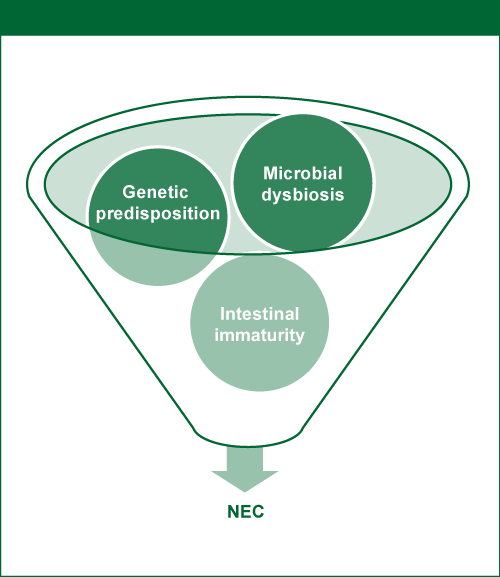

In preterm infants, the onset of NEC is inversely proportional to gestational age, i.e. the most premature infants have the latest onset of the disease. Some combination of intestinal immaturity, microvascular imbalances, abnormal microbial colonization of the gut, and an excessive immune response by the intestinal mucosa to microbial stimuli from the lumen, all appear to underlie the development of NEC in preterm infants (Neu 2014).

Figure 10. Genetic predisposition, intestinal immaturities and microbial dysbiosis combine to induce NEC.

Source: Neu 2014; reprinted with kind permission of S. Karger AG, Switzerland

Intestinal immaturity encompasses immature immune defense, motility, secretion and absorption, and circulatory regulation, leading to a higher susceptibility to tissue injury. Microbial dysbiosis is the inappropriate colonization of the preterm gut. Both of these factors are likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of NEC in preterm infants (Neu 2014).

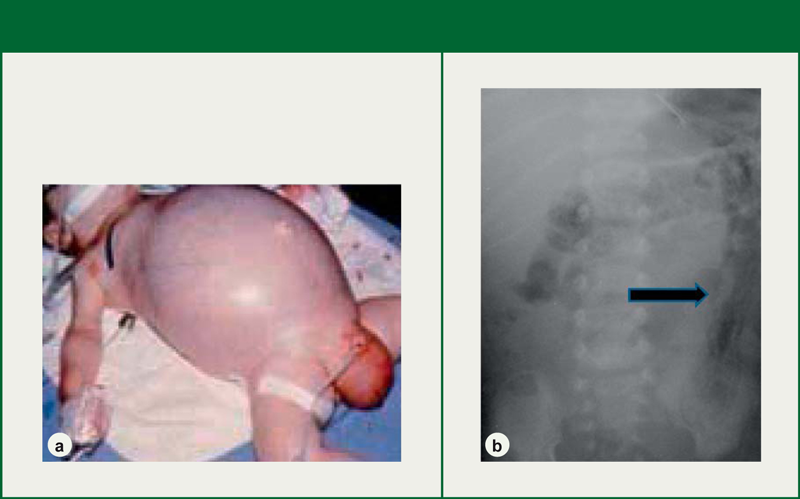

Diagnosis of NEC is difficult as the symptoms of evolving NEC overlap with those of gastrointestinal immaturity. These include feeding intolerance, emesis, bloody stools and abdominal distention. Later, systemic symptoms seen with NEC can resemble those of sepsis. Pathognomonic signs such as intestinal intramural gas (pneumatosis intestinalis), portal venous gas, and pneumoperitoneum can confirm the diagnosis if found on abdominal radiographs or ultrasonography (Neu 2014).

Figure 11: a) Distended, shiny abdomen associated with advanced NEC

b) Radiograph with the arrow pointing to an intestine with pneumatosis intestinalis

Source: Neu 2014; reprinted with kind permission of S. Karger AG, Switzerland

The treatment plan when NEC is suspected includes discontinuation of any enteral feeds and dispensable medications, placement of a gastric tube to decompress the stomach and bowel, monitoring of fluid and electrolyte status, and circulatory support when necessary. Parenteral feed must be initiated with particular attention to providing 3.5-4g/kg/day of protein to support tissue repair, as well as lipids (3g/kg/day) to cover energy needs. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are generally given after blood culture. Surgery is indicated when pneumoperitoneum is present due to bowel perforation, or when general clinical status deteriorates despite appropriate clinical support (Neu 2014). Clinical and nutritional management of NEC will be further discussed in lesson 4.3 in unit 3 of this module.

Preterm infants who survive NEC are at risk to develop intestinal strictures leading to bowel obstruction weeks to months after the acute illness. They may also develop abdominal abscesses, cholestasis, enterocutaneous fistulas and short-bowel syndrome if surgical resection of the necrotic bowel had been performed. The risks of long-term sequelae of preterm birth (Lesson 1.2) are elevated (Neu 2014).

The diagnostic challenge and fulminant course of NEC, as well as long-term morbidity in survivors, make effective measures to prevent this disease critically important. Early nutrition has at least two important roles for the prevention of NEC: provision of human milk to preterm infants whenever feasible and careful introduction and advancement of enteral feeds.

Human milk, which must be fortified in order to meet the nutritional needs of preterm infants, is considered the feeding of choice for preterm infants, in part because of the non-nutritive benefits it provides. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues found that higher proportional intake of human milk in the first 2 weeks of life was associated with lower rates of NEC and death in ELBW infants over 14 days old (Meinzen-Derr et al. 2009). A Cochrane analysis of feeding preterm (<37 weeks) or low birth weight (<2500g) infants with either donated human milk or preterm formula found that formula feeding increased the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis when compared to those receiving human milk, with a risk ratio of 2.77 (95% CI 1.40 to 5.46) (Quigley & McGuire 2014).

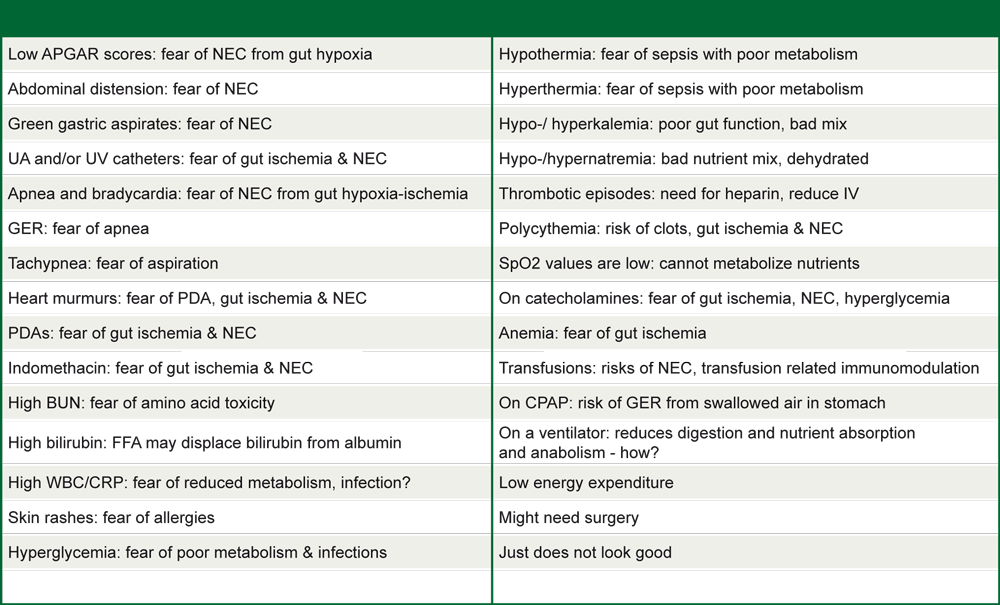

The relationship between enteral feeds and NEC is complex. Fears of causing NEC by introducing or advancing enteral feeds too early or too rapidly, has led to the opposite extreme. A myriad of reasons are given for withholding enteral feeds in NICUs.

Table 5: Thirty random, frequent excuses for withholding enteral feeding of preterm infants

Source: Modified from Hay 2013; reprinted with permission

A Cochrane review by Morgan and collaborators (Morgan et al. 2014a) analyzed nine randomized controlled trials with a total of 1106 infants. There was no difference between the incidence of NEC or mortality in the two groups studied: delayed enteral feed introduction (>5-7 days after birth) and early enteral feed introduction (<4 days after birth). No difference was found also in IUGR infants with Doppler ultrasound evidence of abnormal fetal circulatory distribution. Additionally, infants in the delayed introduction group took several days longer to establish full enteral feeding.

Evidence indicates that delaying or withholding feeds in many cases can actually be harmful. When the immature gastrointestinal tract is not used, the intestinal mucosa atrophies. In preterm infants, development of the gut's capacity to absorb nutrients is delayed, as is development of intestinal motility. The time to reach full enteral feeds is prolonged. The intestinal microbiota and inflammatory response are also altered and the risk of sepsis increases (Neu 2014). In addition, the infant risks under-nutrition and poor growth (see Lesson 2.2).

There is also some controversy about feeding advancement speed and risk of NEC. Another Cochrane review published by Morgan and collaborators in VLBW infants has shown no difference in NEC incidence in the two groups studied: slow advancement with daily increments of 15 ml/kg to 20ml/kg and faster advancement with 30ml/kg to 35 ml/kg. Moreover, the slow advancement group took significantly longer to establish full enteral feeding and regain birth weight (Morgan et al. 2014b).

Other nutritional interventions that may reduce the risk of NEC include: formula acidification and pre- and probiotics (Neu 2014) (discussed in unit 3, lesson 2.5).

Approaches to the introduction and advancement of enteral feeds are described in unit 3, lesson 2.3.