Lesson 2: Benefits of Optimal Preterm Nutrition in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

2.4 Brain

Since the survival rate of preterm infants has increased, the impact of long term complications has proportionally increased. Neurodevelopmental sequelae are the most recognized complication of prematurity and they range from mild behavior and cognitive impairment to severe disability. Most commonly, preterm infants will present developmental delay, learning disabilities, cognitive problems, visual impairment and cerebral palsy. The Institute of Medicine estimates that preterm birth is responsible for 45% of cases of cerebral palsy, 23% of hearing impairment cases in children, 37% of cases of visual impairment and 27% of cognitive problems (Behrman et al. 2007).

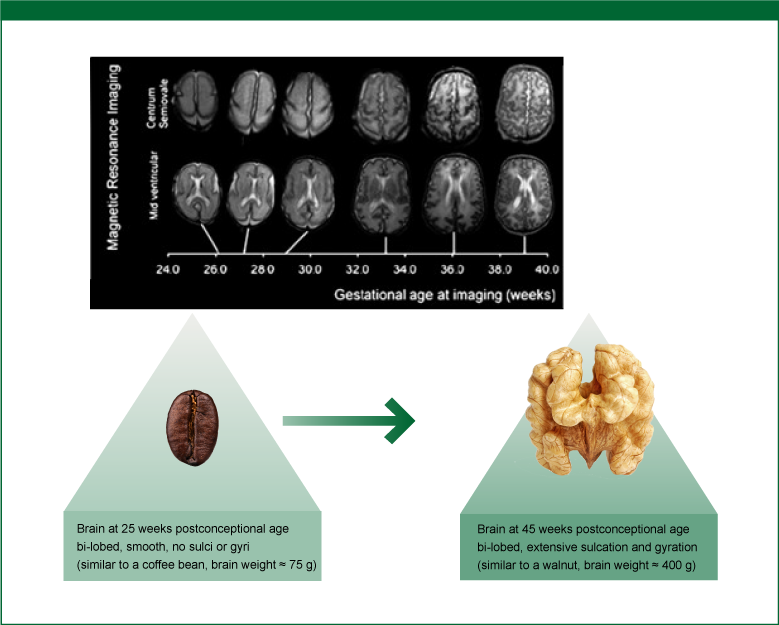

In the preterm neonate, the brain consumes the highest amounts of nutrient resources to feed its high metabolic rate, functioning and growth. Kapellou and colleagues analyzed brain magnetic resonance images of preterm infants between 23 weeks post-conceptional age and 48 weeks post-conceptional age (Kapellou et al. 2006). At 25 weeks post-conceptional age the normal human brain is bi-lobed, smooth without sulci or gyri, resembling a coffee bean. At around 45 weeks the brain looks very different, more like a walnut (Ramel & Georgieff 2014). The surface area has increased remarkably, it is bi-lobed with extensive sulcation and gyration.

Figure 8: Serial MR Imaging of Brain Growth in a Normal Female Preterm Infant.

Source: Modified from Kapellou et al. 2006; reused in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

Although a preterm infant's brain is more able than an adult's to adapt to changes, this plasticity has its limits:

"...[the preterm infant's brain] is also highly vulnerable to insult. Vulnerability generally outweighs plasticity in the developing brain, implying that it is better to continue on a normal developmental trajectory than to fall off and rely on 'catch-up' mechanisms to re-establish trajectory.”

(Ramel & Georgieff 2014)

The goal of nutritional care with regard to brain development is once again to provide the preterm infant with the types and amounts of nutrients to support the same neurologic development in the extrauterine environment as would have occurred during fetal development in utero.

In the previous section the interrelationship of nutrition, growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes was described. When optimal nutrition supports good growth, tracked along IU growth curves, neurodevelopmental outcomes are better. Lean body mass accretion - which can only occur when adequate protein and energy are supplied to the preterm infant - can be used as a marker for structural growth of the brain. Higher lean body mass is associated with faster neuronal processing in preterm infants at 4 months' corrected age (Pfister et al. 2013, Ramel & Georgieff 2014). Poor linear growth in the first year of life is associated with poorer cognitive scores at 2 years' corrected age (Ramel et al. 2012).

Poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in the preterm infant are associated with a number of factors, such as lower gestational age, presence of intracranial hemorrhage, lower weight and height for a particular gestational age, white matter damage, infection and low socioeconomic status. Although the implementation of strategies to diminish some of these risks is routine in the NICU, some are still beyond the control of the neonatal care team. Nutrition, however, is a valuable tool that can be managed in the NICU and is likely to deliver a better neurodevelopmental prognosis (Ramel & Georgieff 2014).

Delivering optimal nutrition to the preterm infant still is a challenge in the NICU. Questions and issues are still prevalent at the time for nutrition management, such as:

What, when and how often to prescribe,

Fear to prescribe what is known to be beneficial to avoid unwanted complications, such as necrotizing enterocolitis,

Failure to deliver what has been prescribed.

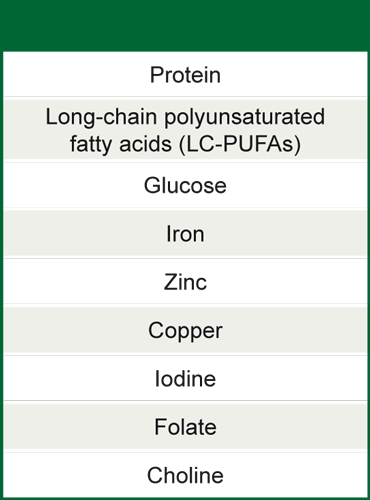

The fetal brain undergoes major developments in the last months and weeks of gestation. During this development some nutrients are particularly important not only in certain amounts but also at specific times ("critical” or "sensitive” periods). In addition, nutrients must be supplied in sufficient but not excessive doses, as oversupply of some nutrients may cause adverse effects (Ramel & Georgieff 2014).

Table 4: Nutrients important for brain development that appear to have a "sensitive period” between 24-44 weeks' post-conceptual age

Source: Adapted from Ramel & Georgieff 2014